by Philip Ferguson

On April 30, 1975 the revolutionary forces of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam and of the supporting North Vietnamese Army (NVA) sent the last US personnel in Saigon scurrying ignominiously to their helicopters at the US embassy and fleeing the country.

What is known in the West as the Vietnam War, but in Vietnam itself as the 30-year long Great Patriotic War, was finally over. The masses had seen off the French and then the Americans. Vietnam was finally liberated and not only had the French been delivered a crushing defeat but US imperialism had too, suffering its first defeat in war.

Origins of the war

Vietnam, along with what are now Laos and Cambodia, was taken over by the French in the late 1800s. The three countries constituted the French colonial possession of Indochina.

In 1941 Japan took over Indochina. The anti-colonial movement, the Vietminh, led by Ho Chi Minh, fought against the Japanese and, after 1945, against the French attempt to resume colonial rule. Between 1946 and 1954, tens of thousands of French troops occupied Indochina, using conventional military tactics, while the Vietminh fought a guerrilla war of liberation.

While the French always assumed they would win a set-piece battle with the Vietminh, this turned out to not be so. At Dien Bien Phu, the Vietminh laid siege to French forces and, after 57 days, forced them to surrender in May 1954. Thousands of French troops were killed, wounded and captured. This battle showed that France simply could not hold onto Indochina against a risen people and mass-based guerrilla war. The French were forced to pull out of Indochina. By this stage the US were already paying 80 percent of the French war cost.

However, at the Geneva conference which followed later that year, Indochina was divided into four states – Laos, Cambodia, North and South Vietnam. Under pressure from the US, Moscow and Peking, the Vietnamese revolutionaries felt they had little choice but to agree to the partition of Vietnam, with Ho Chi Minh and the Communist Party taking power in the north alone. Part of the agreement at Geneva, however, was that in 1956 there would be free elections throughout the whole of Vietnam to reunite the country.

This agreement was stymied by the United States which, by 1954, was already paying 80 percent of the French war costs and beginning to get directly involved. Washington feared that if free elections were held, Ho Chi Minh would win them overwhelmingly and the whole of Vietnam would have a communist government.

Ho Chi Minh would have won

US president of the time, Dwight D. Eisenhower, recored, “It was generally agreed that if an election had been held, Ho Chi Minh would have been elected premier. . . I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indo-Chinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held as of the time of the fighting, possibly 80 percent of the population would have voted for Ho Chi Minh.” (See Dwight D. Eisenhower, Mandate for Change, 1953-1956, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co, Inc, 1963, pp337-38, 372)

In 1960, Vietnamese revolutionaries in the South set up the National Liberation Front, with the aim of reuniting the country and bringing about social change.

In 1960, Vietnamese revolutionaries in the South set up the National Liberation Front, with the aim of reuniting the country and bringing about social change.

The United States’ involvement escalated rapidly under the presidency of John F. Kennedy. He sent a team to Vietnam to report on the situation and what Washington needed to do to protect its interests and deny self-determination to the people of the country. The result of this visit was a White paper in 1961, as a result of which thousands of US covert operations personnel began arriving in South Vietnam.

Dirty work

By 1963 there were 16,000 US “military advisers” in South Vietnam and that same year a coup was organised to get rid of the hopelessly corrupt and incompetent Ngo Dinh Diem and replace him with a military regime more able to do Washington’s dirty work. The new leader imposed by Washington was Air Vice-Marshall Ky.

Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963 and so the dirty work then fell to his successor, Lyndon Baines Johnson. In August 1964, the US fabricated an incident in the Gulf of Tonkin, claiming that the North Vietnamese had fired on US warships. Of course the North Vietnamese would have had every right to do so, since these ships were involved in attacks on the North Vietnamese coast. Indeed, in 1961 the CIA had begun a secret campaign of actions against North Vietnam, Operation Plan 34-Alpha.

Fabricating an ‘incident’: The Gulf of Tonkin Incident

Like the Iraqi “Weapons of Mass Destruction”, the claim made by Washington about North Vietnam attacking US Navy vessels on August 4, 1964 was a fable.

That day a US espionage mission involving several warships (the destroyers the Maddox and C. Turner Joy) in the Gulf of Tonkin, off the coast of North Vietnam, claimed to come under attack by North Vietnamese gunboats. For two hours the US vessels fired on their supposed attackers, but later Capt John J. Herrick admitted a mistake had been made by an “over-eager sonarman” who was “hearing the ship’s own propeller beat” (www.fact-index.com/v/vi/vietnam_war.html).

James B. Stockdale, a pilot of a Crusader jet which carried out reconaissance, reported when asked if he witnessed any North Vietnamese attack vessels, “Not a one. No boats, no wakes, no ricochets off boats, no boat impacts, no torpedo wakes – nothing but black sea and American firepower (Paterson, Thomas, Clifford and Hagan, American Foreign Policy Relations: a history since 1895, 4th ed, Lexington. D.C. Heath and Company, 1995, p410).

Rolling Thunder

The US began ‘Operation Rolling Thunder’, a massive bombing campaign of the North, on March 2, 1965 and continued daily, with only a few short breaks, until November 1, 1968. Curtis LeMay, the US Airforce chief of staff, declared, “we’re going to bomb them back into the Stone Age”, and Washington certainly did its best to fulfil LeMay’s boast.

About 643,000 tones of bombs were dropped on North Vietnam, during that time. Nothing was off-limits: schools, hospitals, churches, and the homes of civilians were all routinely hit by the bombs. The Americans also used anti-personnel bombs – bombs that would explode on hitting the ground and shed layer and layer of cutting edges to do as much damage to human flesh as possible. The idea there was that dead people could be disposed off easily by being buried; that didn’t take a lot of resources on the part of the North Vietnamese. However, inflicting horrendous injuries on large numbers of civilians forced the diversion of a lot of resources from the North Vietnamese defence effort and their support for the NLF in the south. (For an account of what it was like for the people who endured this monstrous bombing campaign, check out Bao Ninh’s novel, The Sorrow of War.)

In April 1965, there were mass landings of US troops at China Beach in the South. The full war was on.

Within several years, the US had over 500,000 troops in South Vietnam, assisted by thousands of allied troops from the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, Australia and New Zealand. In both the US and Australia, the draft was introduced to fight the war. In the US, in particular, it fell on working class, and especially black, youth.

Pro-war youth from privileged backgrounds, like current US president Bush, vice-president Cheney and other members of their cabal used a variety of means, such as college deferments, to get out of being sent to fight a war they supported.

Waging people’s war

The North Vietnamese and NLF recognised that they could not defeat the US using conventional warfare. Nor was there a lot of ‘civic space’ for building an open anti-imperialist movement, revolutionary unions and other oppositional forces in the South. They therefore chose a strategy of protracted people’s war, based on the mobilisation of the whole population of the North and much of the South to take on the US and its puppet regime in Saigon.

The Vietnamese revolutionary forces operated at three main levels:

At the grassroots level in the South, the NLF organised people’s militias. These were guerrilla and self-defence squads and were based in hamlets and villages. As well as fighting, they continued production work, sowing and harvesting crops, for instance. They also supplied recruits to the other levels of forces.

The second level was regional troops. These were the core of armed struggle against the US, its allies and its Saigon puppet forces. The regional troops were organised in strong, high-quality units and were fairly well-equipped. They could operate by themselves or with the militias and regulars.

Regular troops were the third level and included both NLF and regular North Vietnamese (NVA) troops. These were mobile forces which could operate everywhere, from given strategic areas to other parts of the country. They could also wage large-scale battles.

The three sections were organised in proportions which made them especially effective. The revolutionaries, unlike the imperialists and their Saigon adjuncts, had solid bases of popular support, knew the terrain, knew where the enemy was most exposed and thus where to strike. They could concentrate their forces, attack and then melt away into the jungle or countryside. This dynamic mix of forces allowed the NVA-NLF to strike virtually anywhere and everywhere, with anything form compact guerrilla units to large-scale forces.

The protracted people’s war strategy also meant the revolutionaries were fairly self-reliant. They had food supplies, they used home-made weapons and weapons captured from the enemy and they got material aid from North Vietnam, sent down the famous Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Radical anti-Vietnam War movement develops

The successful development of people’s war in Vietnam created the conditions for the growth of a radical anti-war movement in the US. The first protests were organised in February 1965 by Students for a Democratic Society. After this, coalitions of activists – Trotskyists, Maoists, Moscow-liners, pacifists, trade unionists and many unaffiliated young radicals – organised larger and larger protests.

As more and more US troops came home in body bags, more and more Americans began questioning the war and Middle America began to lose its faith in the US government and what Washington was doing in Vietnam. Black America was especially hostile and urban rebellions, of which there were several hundred in the late 60s, became an increasingly common way in which they expressed their opposition to Washington’s oppression of blacks at home and the Vietnamese abroad.

The anti-Vietnam War movement spread across the globe. Mass protests took place in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Britain, and much of continental Europe. Che Guevara went to Bolivia to try to open a ‘second front’ against US imperialism which would help take some pressure off the Vietnamese. Through much of the Third World young people inspired by the Vietnamese (and Cuban) revolutions launched armed struggles for liberation.

The mass movement against the imperialist intervention and barbarism in Vietnam (and Cambodia and Laos) also stimulated the women’s liberation and gay liberation movements, the high school students movement and, in the United States, the new Chicano movement. Local early women’s and gay groups often used the term Liberation Front as part of their name, inspired by the NLF.

This was also noticeable in New Zealand, with groups such as the Christchurch Women’s Liberation Front and the Christchurch Gay Liberation Front. In New Zealand anti-intervention campaigners organised what were, up to that point, the biggest demonstrations in New Zealand history.

Tet Offensive

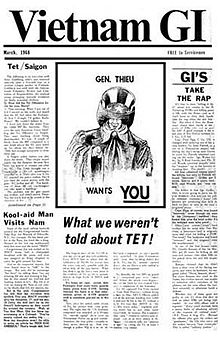

At the end of 1967, the US commander in Vietnam, General Westmoreland, declared that he could see victory in sight. While the government and some sections of the US ruling class breathed a sigh of relief, the light at the end of the tunnel turned out to be the firepower coming from the barrels of the guns of the Vietnamese revolutionaries. In January 1968 the NVA and NLF launched the biggest offensive of the war, the Tet offensive. Hundreds upon hundreds of villages, towns and even important cities were liberated, and the US sent reeling. In Saigon, the revolutionaries even managed to attack the US embassy compound.

Washington was only able to fend off the offensive by the massive use of airpower, bombing liberated urban centres to rubble. Although the Tet Offensive was pushed back, and thousands of Vietnamese revolutionaries, along with ordinary citizens, were incinerated by US firepower and bombing, Tet was a huge moral and political victory for the NLF and North Vietnamese. Essentially, it showed that Washington could never win the kind of war it was being forced to fight in Vietnam. And the way in which it inevitably fought the war was turning people across the world against the United States.

March 1968 saw another event which brought home the brutality of the US onslaught on Vietnam – the My Lai massacre. Several hundred Vietnamese in the village of My Lai were shot to death by US forces and a cover-up orchestrated. Later media exposure forced the top US brass to put a lower-ranking officer on trial and make him take the rap for the whole massacre.

It’s important to remember that US atrocities in Vietnam were daily, most particularly the continuous bombing of cities in North Vietnam and the bombings of villages and towns in the South, and the use of anti-personnel bombs and, in the South, napalm and Agent Orange. This was barely 20 years after the end of World War 2 and, in many people’s eyes, right across the world, the US government seemed to be carrying war crimes as evil as those of Hitler and the Nazis.

Johnson presidency destroyed

By this stage the war had destroyed the Johnson presidency. His programme of social reform, the ‘Great Society;, was undermined by the financial, social and political costs of the war. For instance, the US government had to spend much more than it had in income in order to prosecute the war; this deficit spending exacerbated the country’s economic difficulties as it coincided with the end of the long post-WW2 boom.

The war became more and more unpopular in the United States. Almost wherever he went in the US, Johnson was met by radical anti-war protesters, one of whose favourite chants was “Hey, hey LBJ, how many kids did you kill today.” In March 1968, finished off by the Tet Offensive, Johnson announced he would not be running for re-election that year.

The US election in November 1968 was fought between Democrat Hubert Humphrey and Republican Richard Nixon who promised he’d pull out of Vietnam. Not surprisingly, Nixon won.

However, Nixon’s strategy was essentially to continue the war, albeit with a reduction in US casualties. His policy of ‘Vietnamisation’ aimed at putting ARVN (Saigon puppet regime) troops in the front line, backed up by US training, funding and firepower, thereby minimising US casualties. troops) His policy of ‘Vietnamisation’ aimed at putting the ARVN (South Vietnamese puppet regime troops) in the front line, backed by US training, funding and firepower, thereby reducing US casualty levels.

In 1969, the NLF was in strong enough a position to set up its own government in the South, the Provisional Revolutionary Government. The PRG was given recognition by a number of countries and could offer an alternative regime to the US puppets hanging on in Saigon.

Invading Cambodia

In April 1970, Nixon actually expanded the war by invading Cambodia. The aim was to cut off the supply of aid from North Vietnam that came down the Ho Chi Minh trail, part of which passed through Cambodia and to put a more pliant, pro-US regime in power in Pnomh Penh. Prince Sihanouk was overthrown and the US stooge Lon Nol took power, a move which would eventually result in the coming to power of the monstrous Khmer Rouge regime in 1975.

Across the United States, the invasion of Cambodia was met with renewed massive anti-Vietnam War protests and the biggest student strike in history. Students across the country also occupied buildings and attacked Reserve Officer Training Corps offices on campuses. At Kent State University in Ohio, four white students were shot dead by the National Guard during an anti-war protest. Two black students were murdered by state forces at Jackson State university in Alabama.

Across the United States, the invasion of Cambodia was met with renewed massive anti-Vietnam War protests and the biggest student strike in history. Students across the country also occupied buildings and attacked Reserve Officer Training Corps offices on campuses. At Kent State University in Ohio, four white students were shot dead by the National Guard during an anti-war protest. Two black students were murdered by state forces at Jackson State university in Alabama.

Coming apart

US society was coming apart. Moreover, within Vietnam, the US Army was beginning to disintegrate. US soldiers were increasingly avoiding fighting the liberation forces and even assassinating their own officers, mainly by throwing grenades into their accommodation. By the early 1970s hundreds of “fraggings” were being recorded. AWOLs became common. Drug use was widespread as young American soldiers – the average age of US soldiers in Vietnam was only 19 – tried to escape the horrors of an anti-liberation war into which their ruling class had thrown them.

Members of the US armed forces also began to organise politically. GIs United Against the War had branches in every state in the US by the start of 1972 and uniformed armed forces personnel were increasingly found marching as contingents not off to war but on anti-Vietnam War protests across the country.

The publication of the “Pentagon Papers” by the New York Times in 1971 showed that sections of the US ruling class itself were starting to favour cutting their losses and getting out of Vietnam. The secret documents meanwhile proved that US governments had repeatedly lied to the population; this fuelled further opposition to the war.

Nixon took trips to both Moscow and Peking to improve relations with the Soviet Union and China and encourage them in turn to put pressure on the Vietnamese revolutionaries to moderate their demands and settle for less than the liberation of their country. Washington also stepped up the bombing of North Vietnam, reducing large chunks of its major cities to rubble, in order to put pressure on Hanoi. However, Washington was also in no position to continue the ground war, and most of its troops had to be withdrawn.

In January 1973 peace accords were signed in Paris, marking the end of the war. On the surface it looked like a draw. For instance, the Saigon dictatorship stayed in place. However, the reality was that the liberation forces had won. The US had to withdraw, and the revolutionaries gained a breathing space to partially recover from the devastation and prepare for a later, last push against the Saigon regime.

In early 1975 the final NLF-NVA offensive was launched. The proof that they, not the Saigon regime, had the support of the mass of the people was shown by the fact that the US stooge government collapsed within weeks. On April 30 the victorious NVA and NLF forces marched into Saigon. South Vietnam was liberated and could be reunited with the Nortth.

New Zealand imperialism

The New Zealand government committed troops to the overall imperialist project in Vietnam in 1965. NZ prime minister Keith Holyoake, as it subsequently came out, was not enthusiastic, being rather more clued up than Washington about the difficulties of winning a land war in Asia against a risen people. Nevertheless, especially in the context of the Cold War, New Zealand’s own imperialist rulers were committed to the alliance with the United States which had already replaced Britain as the chief guarantor of capitalist interests in the Asia-Pacific region. NZ troop levels reached a peak of about 550 in 1968. About 3,000 members of the NZ armed forces took part in the invasion of Vietnam over the 1965 – 1975 period. However, unlike in the USA and Australia, conscription was not imposed here.

The anti-Vietnam War movement in this country mobilised against the visit of South Vietnamese military dictator Ky in 1965 but it was not until 1970 that anything like a mass movement emerged. In May of that year there was a nationwide mobilisation against the war, following the US invasion of Cambodia and the My Lai massacre revelations. In April and July 1971, the biggest mass marches across the country took place. The NZ government subsequently announced it was withdrawing troops and its combat forces were withdrawn by the end of 1971, although some military training personnel were stationed there until the end of 1972.

The anti-Vietnam War movement and its growth marked the end of the hegemony of conservative Cold War ideas in NZ society. A new generation with the liberatory ideas of ‘the sixties’ stamped its mark on society, the anti-Vietnam War movement stimulating the beginning of the women’s and gay liberation movements and new organisations of Pacific Islands and Maori radicals. Then old ‘RSA mentality’, associated with militarism and the glorification of war, was on its way out.

Imperialist damage

The imperialists left behind a huge amount of devastation, from which Vietnam has yet to fully recover. Part of the cost of the war to the Vietnamese has been summarised by John Pilger:

“In the South, an enormous area (including 50% of the jungle, 41% of the coastal mangrove forests and 40% of the rubber plantations) had been poisoned by 11 million gallons of chemical defoliant.

“Intricate irrigation networks built over hundreds of years had been blitzed into oblivion. Bamboo villages had been reduced to cinders. Giant B52 bombers had destroyed ports, railways, bridges, hospitals and factories in the North” (See http://pilger.carlton.com/vietnam/war_aftermath).

A greater tonnage of bombs had been dropped on Vietnam than by all sides in World War I, World War II and the Korean War combined.

In addition, some tens of millions of bomb craters were left by the US, while 18 million gallons of poisonous chemicals had been sprayed over countryside and population alike. At least two million Vietnamese and 300,000 Laotians and Cambodians had been killed, over 3 million wounded and more than 14.3 million turned into refugees, as a result of the US war (See http://pilger.carlton.com/vietnam/war_aftermath).

It had taken thirty years of war with two imperialist powers, France and then the US, and millions of casualties, but finally independence had been won.

Response to independence

The imperialists responded with an economic blockade of Vietnam and reneged on their agreement to pay part of the cost of rebuilding the country. The Vietnamese were to suffer further punishment at Washington’s hands. In 1978, US president Jimmy Carter even claimed, “the damage was mutual. . . we owe them nothing” (http://pilger.carlton.com/vietnam/articles/48733).

Additionally, the post-Mao government in China moved closer and closer to the US, even invading Vietnam in 1978.

Forty years on, the success of the Vietnamese liberation forces should continue to inspire. It shows that imperialism can not only be fought; it can be beaten.

Excellent and re-inspiring recap.

LikeLike

Thanks Phil.

I’m sure those of us over a certain age all have vivid memories of the US-led imperialist onslaught on Vietnam and the effect it had on our own lives. The first protest I ever went on was when I was a very young, new high school student. Nixon had just invaded Cambodia and a nationwide mobe against the war took place across New Zealand. I remember the placard with the picture from My Lai and the Q & A as one which was prominent on the march I took part in.

The horror of what “our” side was doing in Vietnam wasn’t the only factor in politicising me, but it was probably the single most significant factor. And there was simply no going back. The system that did what the imperialists, including NZ, did in Vietnam is fundamentally anti-human, the enemy of humankind, and I’ve never seen any reason for changing my mind on that.

The barbarism the imperialists have unleashed, directly and indirectly, on the Middle East is just the most recent reminder of what this system ultimately represents.

Phil F

LikeLike

[…] I’ve written about it here: https://rdln.wordpress.com/2015/04/29/vietnam-40th-anniversary-of-the-triumph-over-imperialism/ […]

LikeLike

Great article Philip, well written.

What’s really interesting here is how we can map the shift from ‘Vietnamisation’ to the use of proxy-forces in the Middle East today. Because of public abhorrence at the like of Mỹ Lai, never again could the reputation of the ‘shining beacon of truth and justice’ be exposed and allowed to come into question in this manner.

In future conflict, either the natives would do the fighting themselves, as far as possible, or the atrocities would be committed by proxy, allowing in turn the added bonus of dehumanising the natives with public opinion at home. This is the genius of current imperialist policy, where we have the so-called Al Qaeda Brigades and Islamic State committing massacres suchas Mỹ Lai.The difference now is the West’s hands are clean and it gives a pretext for military involvement where none is justified.

A great example here might be the ‘execution’ of journalists by ISIL in front of the television cameras. At a time when British-US policy in Syria was running aground, having already failed with the attempt to blame the Assad government for the chemical attack in Damascus, and with the Syrian Army beginning to recover the situation militarily, these execustions served as a pretext for opening up a bombing campaign – a campaign that has resolutely failed to target the Al Qaeda Brigades and has indeed served to strengthen their positions inside Syria. Such military intervention would not have been possible after Iraq without demonising the enemy.

The angle is easy to see if we look closely. Get your proxies to carry outthe Mỹ Lai’s and instead of a public backlash you garner public support for a military strike. Incubators in Kuwait and Gulf of Tonkin eat your heart out.

The whole operation, from Libya to Syria and now into Yemen, is as cynical as it comes and can be seen, at least in part, as a direct outworking of the Vietnam War, its failures and lessons (though of course that’s not to exclude its Iraqi equivalent 20 years later). The response of the American people, as reflected on the ground and in public opinion, and the eventual loss of the war – not on the battlefield but in the key battleground of public opinion – signalled the need to shift tactics: first with Nixon’s use of Vietnamisation and the ‘secret war’ in Laos and Cambodia – later with the use of countergangs and proxy-forces to foment dissent, provoke a reponse, commit atrocity and create a situation demanding direct military intervention.

Seymour Hersh’s ‘Redirection’ is arguably the best place top begin further investigations into this phenomenon.

40 years to the very day from the fall of Saigan we can see that nothing has really changed other than the way in which we conduct the business of war. Millions-on-millions of wasted lives and no end in sight, the European Champions League, the Superbowl or other such trifles of distraction sadly of far greater import to most in our societies today.

It breaks the heart but we’ve no option to keep on reaching out to anyone prepared to listen.

Thanks for the article a chara, thoroughly enjoyed it.

Sean

LikeLike

Very good sum up, what a ghastly picture of imperialist brutality.

The anti Vietnam war protests drew me into radical politics.

There is not the same opportunity for youth today.

The Wellington Committee on Vietnam was led by a small efficient communist group. They inspired young people with big ideas of self sacrifice to make a new and more just world.

Whatever the flaws of our 1970’s vision, we had a clear alternative worth fighting for. That past cannot be recreated in the same way, but until we find a new vision and commitment to realise it our masters have a relatively free hand.

LikeLike