by Philip Ferguson

In recent years events such as the 2008/9 brutal invasion and occupation of Gaza, the blockade on the area and the murderous attack on an aid convoy have raised, yet again, the question of the nature of the Israeli state. The issue is raised among the wider population watching coverage of these events and also poses an important issue for activists concerned with justice for the Palestinians. For instance, in New Zealand, many, if not most, such activists currently don’t openly support an end to the Israeli state itself but, rather, negotiations between the Israeli state and the Palestinian Authority to establish two states. Israel is seen as behaving very badly but this line of thought is not pursued to the logical end that such behaviour is inescapable given the nature of the establishment and development of the Israeli state.

This liberal approach was very evident in 2010 in the campaign against the re-establishment of an Israeli embassy in Wellington. The main campaigning group, NIEW (No Israeli Embassy in Wellington) continually put out press statements suggesting that Israel could be different and if it became nicer then Israel and an embassy would be acceptable. An April 10, 2010 press statement for instance after graphically noting Israeli repression then politically collapsed into declaring, “We should be telling Israel that until they make a genuine peace with the Palestinians we do not want to know them. Letting Israel set up a branch office in Wellington, to pedal its propaganda here, is rewarding its intransigence.”[1]

This liberal view is quite a political step back from twenty or thirty years ago, when activists who took up the issue tended to be more forthright in favour of complete Palestinian liberation. One of the ironies is that the political retreat of activists on the issue comes at a time when public support in New Zealand for Israel has declined markedly. However, the political retreat here among activists around Palestinian rights is buttressed by the political retreat of much of the Palestinian movement itself, most particularly Fatah, the dominant element within the Palestine Liberation Organisation, and thus the PLO itself.

Thus Palestine Authority (PA) head Mahmoud Abbas told a group of Israel intellectuals in Ramallah on Monday (September 5) that the Palestinian Authority’s approach to the United Nations to gain statehood recognition is no threat to Israel – “We don’t want to delegitimize Israel”, he said. Rather, the approach to the UN is taken, he stated, with the peace process uppermost in mind.[2] The PA, Abbas told the intellectuals, would be happy to work with the Israeli state on what Israel would see as security issues and even the finer details of a future Palestinian state. “We will continue to do our job. Security will prevail as long as I am in office,” Abbas continued. Indeed, as he also noted, the Israeli state forces and PA forces have been working together for several years already.[3]

Israel, however, is not impressed. A spokesperson for the Israeli Foreign Ministry responded by saying, “The moment the Palestinians approach the UN and ask for a declaration of statehood they will be violating the Oslo Agreement, which is the framework for our relationship, including our economic relations”.[4] The United States, meanwhile, is attempting to get the ‘peace process’ restarted as an alternative to the Palestinian Authority going to the UN, aware, no doubt, that the Palestinian case for partial recognition of the PA could gain a very substantial majority within the UN General Assembly. There is also a movement within the US Congress to try to get US aid to the Palestinian Authority cut if the PA goes ahead with its case for official UN partial recognition.[5]

The fact that Israel, even with such a lickspittle leadership operating the Palestinian Authority, still oppose Palestinian statehood, even of an inevitably truncated variety, should tell us something about the conditions that Israel requires for its own survival. Israeli intransigence, and the horrors rained down daily on the people of Gaza and the West Bank, are the logical and necessary result of the existence of *Israel as a country, one which can only exist as an exclusivist-Zionist state set up at the expense, and through the dispossession, of the Palestinian people. There is no alternative, more Palestinian-friendly Israel possible.

In order to survive, the Israeli state has to crush all Palestinian resistance to it. Moreover, it has to lower the expectations of the Palestinians and demoralise them into submitting totally to Israeli domination or drive them completely away from the borders of the Zionist state. The necessary consequences of the very existence of Israel, shown to the world so graphically by the assaults on the Gaza Strip, also continually undermine attempts to establish any kind of peace apart from the peace of the grave which Israel requires for the cause of Palestinian emancipation and freedom.

In the past several decades, especially since the Oslo Accords of 1993, the main framework put forward for establishing peace has been the idea of a ‘two-state solution’. This suggested that the Israeli state remain, with its 1967 (pre-Six-Day War) borders, and a Palestinian state be set up in Gaza and the West Bank (the two main areas of Palestinian population occupied by Israel in that war). This ‘solution’ required the removal of Israeli settlers and troops from these areas and the establishment of a Palestinian representative and administrative body.

The two-state project partly reflected the inability of the Israeli state to completely defeat the Palestinians but, more significantly, it represented an attempt by the imperialist powers, especially the United States, to establish stability while maintaining the existence of Israel and continuing to deny self-determination and liberation to the Palestinians. Acceptance of a two-state solution on the part of the Palestinian liberation forces grouped together in the PLO represented a significant political retreat, as we noted above and shall see below.

This two-state approach was not new. For instance, in 1937, when the British government ruled over Palestine under the League of Nations mandate system, a government-commissioned report – that of the Peel Commission – suggested dividing the territory into an Arab area, a Jewish area and an area which Britain would continue to rule. In 1947, the United Nations planned to divide up Palestine along similar lines, their suggestions being rejected by leaders across the Arab world, including in Palestine.

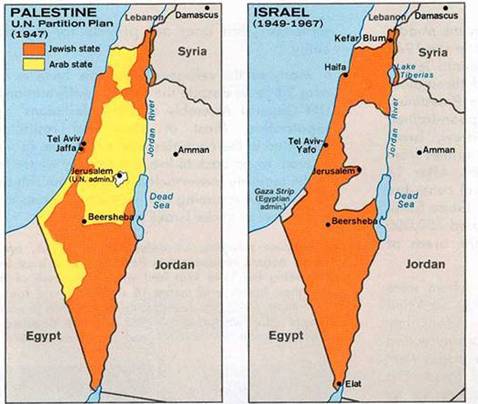

In May 1948, however, the United Nations went ahead with its partition plan. The state of Israel was created and its Zionist creators were given by the United Nations 56% of the territory of Palestine for a Jewish state, although Jews only comprised a third of the population – in fact, when Zionism was founded in 1897 Jews comprised no more than 10 percent of the population of Palestine. The Arab population which comprised almost two-thirds of the population of Palestine were only allowed by the UN to keep 44% of the territory. As the first map below also shows, the whole project of dividing this small land made the proposed Palestinian state unfeasible anyway. Essentially the United Nations had taken more than half of their land and handed it over to a political movement, Zionism, that was essentially a form of European colonialism.

Poorly-trained and -equipped Arab forces, including Palestinians, were defeated over the next eight-nine months. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were driven from their homes and large chunks of what the UN had designated as the Palestinian state were gobbled up by Israel (see maps below). After this war, the new Zionist state had possession of 80% of the land of Palestine. The dispossessed Palestinians fled to other parts of the Middle East and further afield, as well as to the Gaza Strip and the areas west of the Jordan River that were not grabbed by Israel. In 1950, however, Jordan annexed the West Bank region and Egypt took possession of Gaza. The pseudo-state of Palestine – ie, the bit of land left for the Palestinians when the United Nations took away most of their territory – was itself now gone. The Palestinians were left as a people without a country.

Most of the Palestinians driven out of their homeland by the new Israeli state ended up in what were supposed to be only temporary refugee camps, based mainly in Gaza and the West Bank. The camps lacked drainage and sanitation and the inhabitants lived on UN rations.

In 1964, the Palestine Liberation Organisation was set up, by it was dominated by Arab regimes and those they appointed to speak on behalf of the Palestinians. After the ignominious defeat of Egypt, Jordan and Syria in the 1967 war, Israel took over the Gaza Strip, the West Bank and the Golan Heights, the latter being part of Syria (see map below).

It became clear that Arab regimes, even professedly radical ones at the time, such as those of Egypt and Syria, were no match for Israel and could not be vehicles for the liberation of the Palestinians.

Palestinian groups took control of the PLO and it became the main representative body of the Palestinians for the next almost forty years. The PLO brought together a number of different Palestinian freedom organisations. The largest was El Fatah and so its founder and leader, Yasser Arafat, became the head of the PLO. The next most significant force in the PLO was the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), founded by George Habash who came from a Christian Palestinian background. The PFLP officially embraced Marxism.

Over the next several decades the PLO and its various component parts fought an armed struggle with Israel. Their goal, embodied in the Palestinian National Charter of 1968, was to bring an end to the exclusivist-Zionist state of Israel and replace it with a democratic, secular Palestine in which Arab and Jew would live together on the basis of equality. The PLO and its aim of a democratic, secular Palestine also drew some support from radical-minded Jewish people and some small left-wing groups in Israel.

The PLO faced incredible difficulties. Not only was the Israeli state backed by western imperialism, most especially the United States which economically subsidised it and made sure it was armed to the teeth, but the PLO had to contend with an array of reactionary Arab regimes who, however much they disliked the existence of Israel, feared the radical effects of the struggle for Palestinian liberation on their own much-oppressed populations. The more radical Arab regimes gave some backing to the PLO but sought to subordinate the Palestinian organisations to their own political agendas.

From the mid-late 1970s the PLO, which was based in Beirut, Lebanon, came under attack from the Lebanese right-wing Christian military forces, the Israelis and the Syrians and finally, in 1982, were forced to abandon their bases there and move to Tunis. This marked an important defeat for the progressive-secular Palestinian liberation movement. It also made them even more dependent on aid from both manipulative Arab regimes and Western governments which sought to ‘moderate’ the politics and tactics of the PLO.

In the face of these objective difficulties, elements of the PLO, especially in Fatah, began to retreat politically. In fact, by 1974 Fatah had effectively shifted away from the democratic, secular (one-state) solution and towards a two-state approach – the position favoured by both Arab regimes and ‘liberal’ Western governments – although it did not formally adopt a two-state position until 1988. Arafat and the others, removed from the harsher conditions of Beirut, also began to enjoy the comforts of Tunis and the opportunities for personal enrichment and high-flying diplomacy that were opened up to them as they shifted away from the perspective of a liberated Palestine and towards accommodation with the existence of Israel.

In 1988, Arafat addressed a meeting of the UN in Geneva, formally announcing PLO recognition of Israel and declaring it should be able “to exist in peace and security”. He also announced that the PLO “totally and absolutely renounce all forms of terrorism. . .” In reality, he was declaring an end to all armed struggle against Israel. The aim of the dominant leadership of the PLO then became the establishment of a Palestinian state alongside Israel.

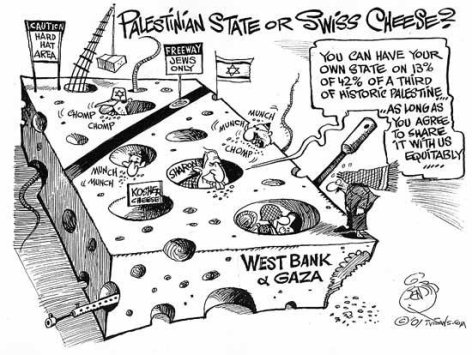

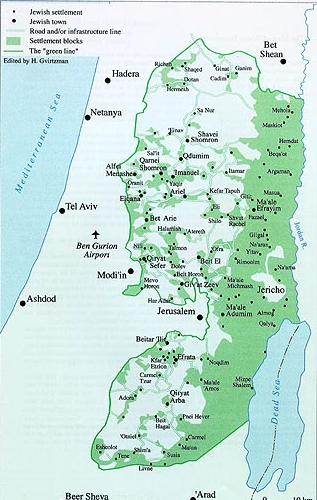

Such a perspective, however, ran counter to any possibility of Palestinian liberation. For a start, from the time of the 1967 war, Israelis established settlements in the Occupied Territories and saw these as part of a Greater Israel. These settlements spread out, especially across the West Bank, in a way which broke up the Palestinian territories. Even travel between Palestinian towns is hampered by Israeli settlements and road blocks. It was and remains impossible to form any contiguous, even half-viable Palestinian state and economy. Moreover, given the levels of poverty among Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank, many had little choice but to commute daily into Israel for work, becoming a source of cheap labour for the Israeli economy. In practice, the Palestinian areas became something life a series of Bantustans, under the economic, military and political thumb of the Israeli state.[6]

However, since the dominant ethos of Zionism has been more to push the Palestinians away from Israel’s ever-expanding borders than to use them as a mass pool of cheap labour, the apartheid/Bantustan analogy can be misleading. As Israeli-born Marxist Moshe Machover has noted, the Palestinian areas are more like the Native American reservations created by the US government, in terms of their political and economic function, than they are like Bantustans.

In 1987, Palestinians frustrated by the continuing Israel rule and oppression of the Occupied Territories rebelled. In particular Palestinian youth took on the Israeli military with stones, petrol bombs and other improvised weapons. The rebellion was called the Intifada. The next year, the king of Jordan renounced Jordanian claims over the West Bank in favour of the PLO.

Peace talks about establishing a formal Palestinian state got under way in the early 1990s, resulting in the Oslo Accords of 1993. The immediate background to these accords was the increasing political pressure being placed on the PLO and the increasing corruption of the leadership around Arafat. The collapse of the Soviet bloc, one of the PLO’s most important backers, and the withdrawal of financial assistance by the Gulf states due to Arafat’s support for Iraq in the first Gulf War, meant that the PLO found it increasingly difficult to survive and manoeuvre; it became increasingly dependent on winning some kind of favour from the US and other Western governments and doing a compromise deal with Israel.

The Oslo Accords envisaged a partial shift to Palestinian self-government in the Occupied Territories. It was only partial because parts of these areas would stay under full Israeli control (eg the substantial Israeli settlements) and parts under Israeli “security” control. Issues such as the settlements, the fate of Jerusalem and the question of the return of Palestinian refugees from abroad, of whom there are several million, were left to be decided upon at a future date. In 1994, a Palestinian National Authority (PNA) was established as an administrative structure in the Bantustan-like Palestinian areas of the West Bank and Gaza and the following year Arafat was elected as its first president. The PNA received substantial funds from the US and the European Union – about $US1 billion in 2005, for instance – although chunks of this money ended up in the hands of the Arafat cabal and their friends in business. Indeed, the PLO became increasingly corrupted by the funds which sections of its leaders controlled through the PNA.

The increasing corruption and collaboration of much of the PLO leadership with Israel paved the way for the rise of Islamist movements such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad, especially in Gaza, the poorest of the two main Occupied Territories/PNA areas. Hamas emerged in 1987, during the first Intifada.[vii] It arose from the Gaza wing of the Egyptian-based Muslim Brotherhood. It gained a mass base by being seen as an intransigent opponent of Israel and Israeli oppression of the Palestinians, because it provided social, cultural and economic services to the Palestinian population and because it was untainted by the corruption associated with the PLO. When the Second Intifada began in September 2000, it swelled the ranks of Hamas and other groups which were seen as more strongly asserting Palestinian rights than the PLO. In 2000 the Islamic Hezbollah movement drove Israel out of Lebanon, where it had been esconced since invading that country in 1982. This further raised the prestige of Islamic politico-military forces.

In 2006, Hamas won the PNA elections, displacing the PLO as the major representative party of Palestinians, at least within the areas nominally under PLO control. The Western powers expressed their displeasure with the democratic vote of the Palestinian people and cut off aid to the PNA. The economic position of the Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank has deteriorated even further. According to the latest World Bank report, the percentage of Gazans living in ‘deep poverty’ rose from 21.6% in 1998 to 35% in 2006, while GDP growth is zero. GDP per capita in Gaza is under $US600 a year at present and possibly double that in the West Bank compared to around $30,000 in Israel. Unemployment ranges from 40-50% in Gaza and over 20% in the West Bank, compared with just over 7% in Israel.

The economic statistics for Gaza and the West Bank point up how unviable a two-state ‘solution’ is. This solution means a Palestinian pseudo-state, with mass poverty and unemployment and chronic under-development alongside a prosperous Israeli state which would continue to be armed and supported by the United States and other Western powers. The Palestinian pseudo-state would be thoroughly subordinate to Israel and dependent on aid from Western powers. It would continue to provide cheap labour whenever Israel needed it, and such workers would be commuting daily between home in the impoverished pseudo-state and work in Israel. Whenever the resulting Palestinian anger targeted Israel, the governing apparatus of the Palestinian state would be expected to crush it. In effect, such a state apparatus would police the Palestinian population on behalf of the Israeli state. To a large extent, this is the role that the PLO/PNA played in the late 1990s and early 2000s and helps explain the loss of support for the PLO. Whenever the Palestinian Authority proved incapable or unwilling to play such a role, the Israelis would intervene directly, with their regular bombs, their phosphorous bombs, their tanks and other military might to teach the Palestinians their ‘proper’ place.

All the current repressive activity by the Israeli state is thus the logical product of the two-state solution imposed by the imperialists and agreed to by the Arafat cabal atop the PLO. The Palestinians can never hope to be liberated politically, much less economically, by a two-state set-up. The fight for a single-state solution therefore seems to be making a comeback, much to the chagrin of the Israeli establishment.

Interestingly, back in 2003 Israeli deputy prime minister Ehud Olmert – he later became Kadima prime minister – told the country’s leading newspaper, Haaretz, “More and more Palestinians are uninterested in a negotiated, two-state solution, because they want to change the essence of the conflict from an Algerian paradigm to a South African one. From a struggle against ‘occupation’, in their parlance, to a struggle for one-man-one-vote. That is, of course, a much cleaner struggle, a much more popular struggle – and ultimately a much more powerful one. For us, it would mean the end of the Jewish state.”[7]

Speed the day.

Notes

1. See: http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO1004/S00340.htm

2. See “Palestinian statehood ‘essential for success of Israel peace negotiations’”, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/palestinianauthority/8745752/Palestinian-statehood-essential-for-success-of-Israel-peace-negotiations.html

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. I use the term partial recognition because the Palestinian Authority is seeking observer status rather than full membership at the UN. For aid threats, see http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/palestinianauthority/8733109/US-Palestinian-aid-could-be-cut-if-it-continues-to-seek-statehood.html

6. The Bantustans were set up by the South African apartheid government. They were impoverished areas of nominal black self-government, but in reality controlled by puppets of the apartheid regime. Workers were sucked out of and pushed back into the Bantustans as cheap labour at the will of the (white) South African capitalists. [vii] Ironically, there is quite a bit of evidence that Hamas received Israeli backing in order to undermine secular radical Palestinian nationalism, which the Israeli state saw at the time as the main threat. While the PLO made compromise after compromise, none of it was enough for the Israeli state; it continued attempting to destroy Arafat and the PLO. One of the results of this is that Israel now faces a substantial, militant Islamic movement.

7. See: http://www.haaretz.com/general/maximum-jews-minimum-palestinians-1.105562

I believe a one state solution is best, as it will actually bridge the gap between two peoples, rather than just continue to separate them. Instead of forging distinct borders between where Jews can live and where Arabs can live, we need to work for a common country that will give these people a common bond that will work to the benefit of both peoples.

It will be more difficult, but the day Arab and Jew can live as equal and as brothers will be the day of great celebration and will serve as a great victory against the reactionaries of both sides of the conflict.

LikeLike